When disseminating critical information during times of crisis or danger, it is crucial to use the best visual communication practices possible. The importance of this concept is evident when comparing how two publishers visually represented key weather information regarding Hurricane Irene in the US.

Where’s the potential danger?

During an impending weather crisis, residents need to know what will happen in their immediate locale in order to prepare for potential danger. They may also seek detailed weather information where family and friends reside or how the weather will affect travel plans. The bottom line is that when people choose to view a map, they are seeking greater understanding.

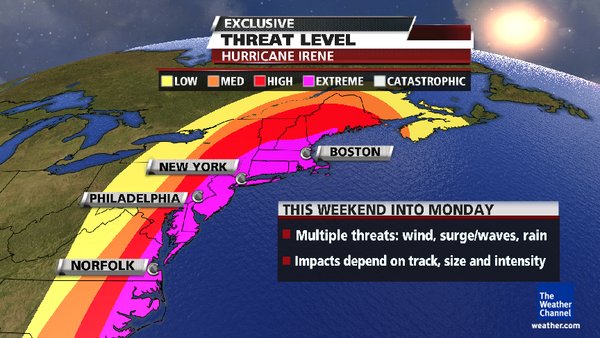

Disappointingly, The Weather Channel maps provide a broad overview of Hurricane Irene—one that is not particularly useful to anyone needing detailed information. To get the outlook for weather in a specific area, users of this website must seek textual information or use a radar map sometime in the future as the hurricane approaches.

In The Weather Channel map below, the big picture view of the hurricane doesn’t provide much more detail than a headline. From this map, we gather that there will be a strong hurricane headed up the Eastern part of the US. The problem is, we already knew that, which is why we came seeking additional information in the first place. The labels indicating the time of the path are helpful, but are difficult to interpret because of the lack of map detail.

Dense Visual Language

In the map above, the red streak of the hurricane will catch the viewer’s attention and indicate the general predicted path of the hurricane. Yet the saturated colors surrounding the red streak detract from the contrast and thus, its impact. Most viewers are aware that the ocean lies East of the continent and that a solid land mass lies to the West. Were the map more subdued, the contrast would be greater. In addition, the underlying state boundary lines—the information readers are seeking—are nearly impossible to discern. Most importantly, there is no functionality for enlarging the map or for zooming in. This should be a requirement for weather maps. Essentially, no detail can be found using The Weather Channel map.

To be fair, there are a selection of weather maps available at The Weather Channel site. For example, see the map of potential threat levels below. Using the key, viewers can determine the potential threat risk if they live in or near one of four cities. Hopefully, no one lives near or around Washington DC, a region that apparently was not deserving of a label. It seems to me that only presenting a big picture view fails to take the users’ needs into consideration.

Nuanced Visual Language

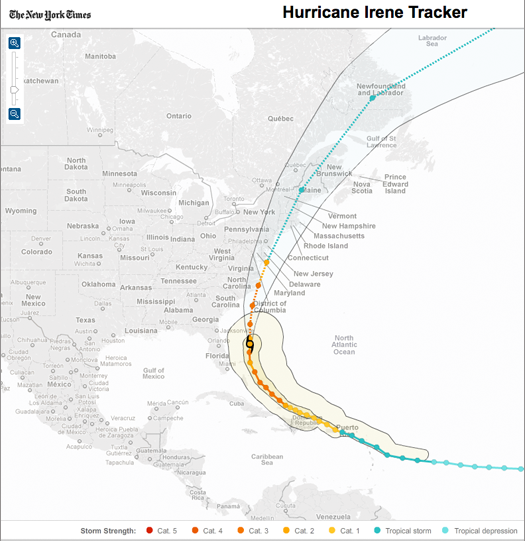

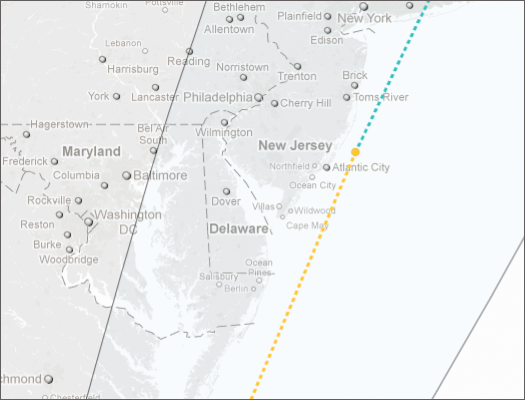

Let’s compare this to the map implemented by the NY Times below. With a quick scan, the viewer can see the predicted path of the hurricane as it relates to specific regions, because the path is transparent and the map provides needed detail. This approach gives us the two layers of information that will most likely answer the question, “What’s happening where I live?”

In addition, by establishing the map in a neutral color, readers can focus on the high-contrast dotted line of the hurricane’s path. Using a color key, the map provides additional information about the category of storm in each region. For those who cannot differentiate between these colors, there is an interactive component to provide information. Also note that the current path of the hurricane is shown with a solid line and the potential path is indicated by a dotted line. Visually literate readers understand that a dashed or dotted line in this context indicates something that does not yet exist.

Interactivity

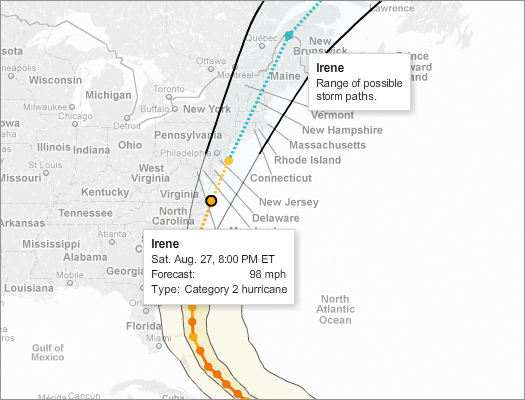

Another obvious advantage to the NY Times map is its interactivity (see below). A mouse-over on one of the darker lines explains that it is the outside range of the paths the storm could take. Also, moving the mouse over one of the colored circles on the main path provides a more detailed time estimate of when the storm will hit the region. I assume this approach will suffice for people with impairments in discriminating colors.

The map is also equipped with a typical slider for zooming in and out (shown in the first NY Times map above). In the close-up view below, the potential path of the storm in my region of interest becomes apparent. Finally! I got the information I was seeking.

Conclusion

In summary, the aspects of visual language that were effective include: 1) detailed and overview perspectives, 2) high-contrast colors when indicating areas of critical information, 3) information presented in layers, 4) dotted lines to indicate what will potentially occur, 5) attention to accessibility issues and 6) interactivity that provides meaningful information.

I realize that this analysis didn’t take into consideration the budgets of both organizations, which I have no way of knowing. But I suspect that a channel devoted to the weather could do more if they paid attention to the needs and wishes of their users and then provided solutions using the subtleties of visual language.

{ 10 comments… read them below or add one }

Sadly, this is an example of putting entertainment value ahead of information value. Great article and analysis of the informational value of color and saturation.

Hi Bruce,

That’s an interesting way to look at it. Thanks for your comment.

Connie

I wonder how much of these two approaches to displaying information on Irene is based on the different cultures of print journalists vs. broadcast journalists. Even though both examples are posted on the individual organizations’ web sites, they are still very indicative and exhibit many of the traits of their main forms of media (printed newspapers for the NYT and television broadcasts for TWC).

The NYT map would, for the most part, look right at home in the pages of the Times’ print edition (minus the interactivity of course), and, if I had to guess, the examples from TWC were most likely used as stills in their TV broadcast and repurposed for the web site (despite the opportunity to add interactive functionality).

In general, broadcasters have always shied away from the fine details of a story in favor of broad, general strokes, while print journalists are all about advancing the story, looking ahead and giving as much detail as possible. The interesting thing to me is that it seems those generalizations are playing out on the web as well.

While I agree that from a strictly information design-centered point of view the Times’ map is far superior in terms of usability and readability, I wonder which site has gotten the most eyeballs during the coverage of the storm. My bet is on The Weather Channel, but that’s a complete shot in the dark.

Hi JT – I *love* your insights regarding print versus broadcast … that the inherent nature of each type of media influences the publisher’s web product. Yet the NY Times had the smarts to add interactivity and The Weather Channel isn’t there yet. I’m sure the latter got more views, which is even more reason why they should be thinking about their users’ needs, IMHO. Do you think so?

I expected them to provide more information and they were the first place I went. When I didn’t find what I needed, I looked elsewhere. They’ll be losing website visitors if they don’t up the quality of their maps. Thanks for taking the time to add to the conversation.

Best,

Connie

Connie,

I do think in an ideal situation that TWC’s approach would have more closely resembled the NYT’s. The NYT map was, without a doubt, far superior and a lot more usable, but I’m not so sure TWC will lose as many (or any) visitors to their site because what they posted was “good enough.”

I read an article back in 2009 in Wired called “The Good Enough Revolution.” If you Google it you’ll get the URL. Basically it focused on a lot of different technology that was seemingly inferior to other alternatives in the marketplace, but, despite that, became the most popular and in some cases the de facto standard.

Just because someone offers something better doesn’t mean people buy it or use it more than something that’s “inferior.” I could make the argument that the depth, clarity and detail of coverage a newspaper delivers beats the quick sound bites of television every day of the week and twice on Sunday, yet the newspaper industry is rapidly plunging into oblivion/irrelevance.

If we agree that the NYT’s map was far superior than what TWC offered up, why does TWC get more eyeballs on it’s website (according to the Wall Street Journal the NYT site attracts 30 million unique visitors per month, while TWC attracts 45 million per month according to their media kit)? I know that’s not an apples to apples comparison, but I guess my point is just because someone offers something bigger, better, with more features and that’s easier to use doesn’t mean they win the hearts and minds of the masses.

Sometimes all the masses want is for it to be good enough, which is kind of what Bruce was saying with his comment.

I agree that website visitors do not always go for something superior. But I don’t think you can compare the TWC traffic with NYT, as even though the map was poor, people go to TWC for daily weather, which they more or less provide appropriately. (I actually have a complaint about how they use rainy icons when there’s only a 30% chance, but that’s another story.) So TWC appeals to a larger population base than does the NYT, regardless of the quality of their maps. In fact, perhaps that’s why they don’t care. Who knows?

Yeah, the web traffic comparison I made isn’t a great one, but when you say, “So TWC appeals to a larger population base than does the NYT, regardless of the quality of their maps. In fact, perhaps that’s why they don’t care,” is my point exactly.

TWC doesn’t need to make their maps any more readable or usable. The masses don’t really care about the added value that some places like the NYT offer.

But I guess the question of whether TWC would benefit if they “paid attention to the needs and wishes of their users” was only a small part of your original post and certainly not the main idea. I didn’t mean to get the discussion bogged down in that minor detail.

No prob. Fun talking to you!

Conny,

great article !. I was wondering, would something like crowdmapping (for example: this http://irenerecoverymap.com/main ) be more suitable for the purpose of information sharing ?

I like that there is some criticism of weather.com. For people who deal with life saving data on a daily basis, they certainly could use some more critical analysis to help improve their communication.

Given that we can all agree TWC is behind in their visualization quality, a comparison of some good hurricane visualizations might be useful. Stamen Design put out a rather nice tracker for MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26295161/ns/weather/t/hurricane-tracker/

It would be interesting to hear your thoughts on their interface in comparison with the Times’ map. I think the audience comparison would be much more relevant, and the interactions are equivalent rather than being wholly one sided.

-Drew